Back in the Saddle

Back in the Saddle

Covid, Blogs, and the Future more Generally

On the other side of a year back at Uni, now, which goes some way in explaining why this blog has been idle since last summer. Pleased to say that I didn’t find it overwhelmingly difficult at any stage, but I was still reticent to divide my efforts – I was already trying to keep up with music and physical activity, so writing with any regularity would have been maybe a bit much.

However, as everyone is no doubt aware, things have changed up since then, and I find myself with a profusion of free time. These last weeks have been spent tying things off with the academic year – my situation is somewhat unusual as I’m sat between two universities, and, at the moment, between two degrees, but that is shaping up as the days pass. Also, alongside just about everyone else, I’ve been coming to grips with our new, COVID-19 reality. We’ve moved back to Canada, which has not been hit as heavily as many other industrialised nations yet, and our particular slice of it has fared even better than average, but the change to schedules, the psychic space, expectations for the future all take time to adjust oneself to. But, even as provinces and states move to re-open (grossly prematurely, to my estimation), get our feet under ourselves we do.

More than just growing acclimatised to the new weirdness and searching for semi-productive ways to spend my time, though, it was a recent read by way of Cory Doctorow’s blog that has me coming back here.

If you’re a long-time reader, my enjoyment of weblog extraordinaire BoingBoing shouldn’t be news to you. Unfortunately, over the past half-year or so, I’ve had the niggling feeling that quality has been dropping off: unlike most spaces on the internet, I’ve elected to turn off the adBlock when I visit there, under a likely-misguided belief that they deserve my clicks more than other sites, but, between the rapacity of the ads and the growing use of auto-play and pop-up videos, the viewing experience is falling off a cliff. Likewise, though more difficult to track, it feels like the quality of content has decreased – less interesting posts, and those that do make it through lacking the previous character and nuance.

As it turns out, Doctorow – one of the key figures over the site’s multi-decadal history and a large impact on its left-wing, tech-philic anarchic flavour – has been disaffiliated since at least some point in February, if not earlier. It’s unclear whether this was due to the direction the site was taking, monetising more deliberately with advertorials often in direct contraposition to other content, or if it was down to a disagreement amongst editing staff (though, as I said, nothing is clearly laid out insofar as I can tell, it seems that he and other core-BB member Xeni Jardin may stand on opposing sides when it comes to the conduct of Glenn Greenwald and the Intercept’s handling of whistleblowers), but in the end it doesn’t much matter: no longer is he there and it seems the worse for his departure.

All this to say, I’ve started frequenting the personal blog he keeps at pluralistic.net, a stripped-back, almost retro-internet space that is dedicated to making good on what Doctorow espouses –

One recent piece discussed the end of another blog space, that of ‘Beyond the Beyond,’ the regular column hosted by Wired where cyberpunk giant Bruce Sterling would regularly dump his brain. Apparently Condé Nast have been hit so heavily by the economic results of COVID that they are jettisoning even unpaid blog spaces to stay afloat (get a year’s subscription to Wired, 88% off!), and so it must go. I’d not been a frequenter of Beyond the Beyond before its demise, only ever really have a passing interest in cyberpunk and its luminaries, but the eulogy prepared by Sterling was interesting in-and-of itself, and a portion in particular stuck out for me, on the nature of blogs more generally:

Unlike most WIRED blogs, my blog never had any “beat” — it didn’t cover any subject matter in particular. It wasn’t even “journalism,” but more of a novelist’s “commonplace book,” sometimes almost a designer mood board…It’s the writerly act of organizing and assembling inchoate thought that seems to helps me. That’s what I did with this blog; if I blogged something for “Beyond the Beyond,” then I had tightened it, I had brightened it. I had summarized it in some medium outside my own head. Posting on the blog was a form of psychic relief, a stream of consciousness that had moved from my eyes to my fingertips; by blogging, I removed things from the fog of vague interest and I oriented them toward possible creative use.

I’ve a few of my own, physical zibaldones kicking around, but they seldom require of one the sustained attention that a proper blog does, and certainly don’t have the flexibility underlined by Sterling – no ctrl+f, no hyperlinks, certainly no possibility of any interaction with a public. I don’t assume a large readership here – in fact, if you do find your way here, I’ll assume you made a wrong turn at some point. I don’t actively advertise the site, haven’t optimised the URL or the content for search-friendly traction, and, honestly, never really intended it to be otherwise. As such, I’ll continue to use this spot in the spirit Sterling outlined above – a clearing-house for my thoughts, where I can mull things over in long-form that I wouldn’t otherwise be able to do with such ease.

If you’re still along for the ride, you’ll be pleased to know I’ve finally completed Ronald Purser’s McMindfulness, and should have something on that in the next few days after chewing on it a bit. I haven’t yet finished Kabat-Zinn’s Full Catastrophe Living, which should make for interesting reading following the evisceration Purser subjects him to. Otherwise, I’m nearly through Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum, and I feel like my understanding of that novel almost necessitates digestion and regurgitation, cud-like, just to try and make sense of it. Lastly, I’ve recently come into possession of a fresh collection of essays on Erich Fromm, and I suspect that will, in one way or another, make its way here eventually.

There may, heavens forfend, even be a return to fiction at some point.

Triratna – Worse than We Thought

This article was posted on the Guardian’s site Sunday, detailing acts of sexual misconduct in the Triratna Buddhist organisation much broader than initially revealed in the 1990’s. I’ve written about this before, when talking about Triratna and their former leader, Sangharakshita, but it seems that the issues extend beyond just his own transgressions, and that they have in some ways been obfuscated by the group. The meaning of Sangharakshita, ‘one who is protected by the spiritual community,’ is looking rather apropos, it seems.

The latest revelations come as reports by both current and former members interrogate the extent of abuse and the lack of appetite to tackle the issue effectively. It seems that “more than one in 10…claim to have experienced or observed sexual misconduct while in the order.” This is both in the UK and abroad, naming Sangharakshita and other high-level members, and, crucially, against both men and women, whereas the initial allegations pertained only to men.

Included at the end of the article is an excerpt from one of Triratna’s own, internal documents from the 1970’s, a theoretical precis on the need for separation on the part of new adherents from their original families. Obviously, this has been selectively edited, but material like “The young man has to realise that he must submit and become totally passive to that which will liberate him from the domination of his mother” and “Many ‘mummy’s boys’ have a fear of passivity in a homosexual relationship even though that is what they may naturally want,” are difficult to read as anything but efforts at grooming.

The article references the hedonistic nature of the early and mid-period Triratna spaces, describing them as “more reminiscent of a San Francisco gay bath-house than a Buddhist retreat.” This gets me to the crux of my worry – what is it about these organisations that leads to this abuse, which we see again and again, whatever the stripe of religion? Is there something in the hierarchical structure that protects abusers? What makes purportedly spiritual life so attractive to people likely to abuse? When I read it initially, it didn’t seem so distressing, but when Alan Watts says “…the sexuality of the bodhisattva is limited only by his own sense of good taste and by the customs of whatever secular society may be his home,” in his work Psychotherapy East & West, is this part of the issue, the belief that, having attained some personal revelation, the onus becomes more about what the individual chooses, rather than the restrictions of society?

I’m more than a dozen episodes deep in to Prof. John Vervaeke’s ongoing video series, Awakening from the Meaning Crisis, which, amongst other things, focusses on the ways in which historical paths of wisdom, including Buddhism, can be used to address thoroughly modern problems. The way Vervaeke weaves these strands together with the findings of current cognitive science results in a compelling argument, but I continue to be assailed by doubts. I’ve felt these for a while, initially about the character of supposed sages (such as the previously mentioned Alan Watts, who struggled with alcoholism – an affliction shared with the originator of the Shambhala school of Buddhism, Chogyam Trungpa) but the fresh revelations about Triratna point to yet another aspect. If, indeed, we have access to the tools to surpass the worst parts of us, to better ourselves and the world, and have had them for literal millennia, why are we here, in this shitty place, today? How do we reconcile the high-octane theoretical and abstract material that we see presented in arguments such as Prof. Vervaeke’s, with the lack of uptake in the material world? Does this in any way undercut the validity of these approaches, the fact that they haven’t yet achieved their emancipatory potential, that, worse, the people who purport to practice and safeguard them are continually found to act in antithetical ways?

I honestly don’t know the answers to these questions.

I recall Erich Fromm writing in To Have or to Be? that, in all likelihood, our civilization was doomed to destroy itself – even more prescient with the environmental crisis we find ourselves in, when he was only concerned by the possibility of nuclear war (still on the table, of course). However, Fromm also argued that we have at least the sliver of possibility if we radically reorient ourselves. It may be that the paths of wisdom Vervaeke is presenting are still our best bet, alongside and combined with a massive shift in how we organise our world. Beats the alternative of doing nothing, I guess.

Recent Additions

In other news, I stopped by one of London’s many metaphysical shops before we quit the country, picking up Kabat-Zinn’s Full Catastrophe Living and Alan Watts’ Psychotherapy East & West, so expect eventual commentary on those once I’ve made my way through them. Given the last post, should probably get to grips with the beasts that started it all.

Contra Mindfulness – A Quick Comment on the Rash of Anti-Mindfulness Articles

Over the last few years there has been a growing number of voices decrying the mainstream adoption of Mindfulness. Insofar as I’ve seen, these are generally people politically affiliated with the Left, concerned that the stripped-back, purportedly ethics-free version of Mindfulness is being deployed by the State and by Industry more largely in ways that are disingenuous at best and actively malicious in more extreme cases. There are also voices decrying the way in which Mindfulness, transmogrified for Western palates, is being perverted by removing it from the ethical and soteriological grounding in Vedanta and Buddhism, resulting in a mere technique where once was an holistic world-view.

Examples of the ways in which Mindfulness could or has gone wrong run the gamut – from broad-stroke worries about the ways in which focus on the self disconnects us from larger social concerns, exemplified in military training or, you know, that monster Sam Harris, to the hand-washing benefits it grants existing power structures, such as the shockingly cruel example of a local council selling off affordable housing, and then providing the former occupants life-coaching workshops to treat their stress, thus presenting themselves as a solution, rather than the source of the problem in the first place. To get a feel for how established Mindfulness’ cachet is, look no further than the way other cultural institutions are trying to benefit by association, such as Museums, critiqued here (following a quick search, it looks like critiquing Mindfulness has become something of a cottage industry over at The Baffler).

For my part, I find myself open to both these criticisms, that of misuse and of inappropriate or insufficient presentation, but am probably more inclined to the former. Stephen Batchelor has long argued that a modern, secular Buddhism can be crafted to find fertile ground in Western soil, without losing its core nature or mission, that in fact this has always been part of Buddhism’s multi-millennial character, fitting itself into its host society to most effectively communicate itself in the local parlance. So, with that in mind, I think that that hurdle can be addressed – though obviously what we’re currently seeing is falling far short of the mark.

As I think I’d mentioned before, I’m gearing up to start training in psychotherapy, so the larger issue is something of a concern for me – am I going to be investing time and money, only to unwittingly perpetuate the ills I’m hoping to cure? What I’m finding frustrating about a lot of these articles is that they are merely pointing out the possibility for abuse, or indeed documenting the abuses already being committed, without pointing a way forward. I’ve had conversations both online and in person regarding this, and maintain that Mindfulness training is a useful tool, and not one we should give up on merely because it is currently being misused on an industrial scale, unfortunate as that is. The fact remains that it demonstrably improves people’s lives in a measurable way, as I’ve seen in my own life and in data.

Of late, a number of the articles have been pointing to the recently published work McMindfulness, written by Ronald Purser, which “argu[es that] its proponents have reduced mindfulness to a self-help technique that fits snugly into a consumerist culture complicit with Western materialistic values.” Purser is a Professor of Management at San Fran State University which I, uh, am left a little dubious by, but he seems to talk the talk alright, with a publishing record in the appropriately Leftist/rad-lib journals and sites, and is purportedly a long-practising Buddhist, so at least should know what he is talking about on that score. I’ll try to grab a copy at some point, but I’m hoping for something more substantial than simply a book-length version of the same formulaic article we’ve been seeing for years now.

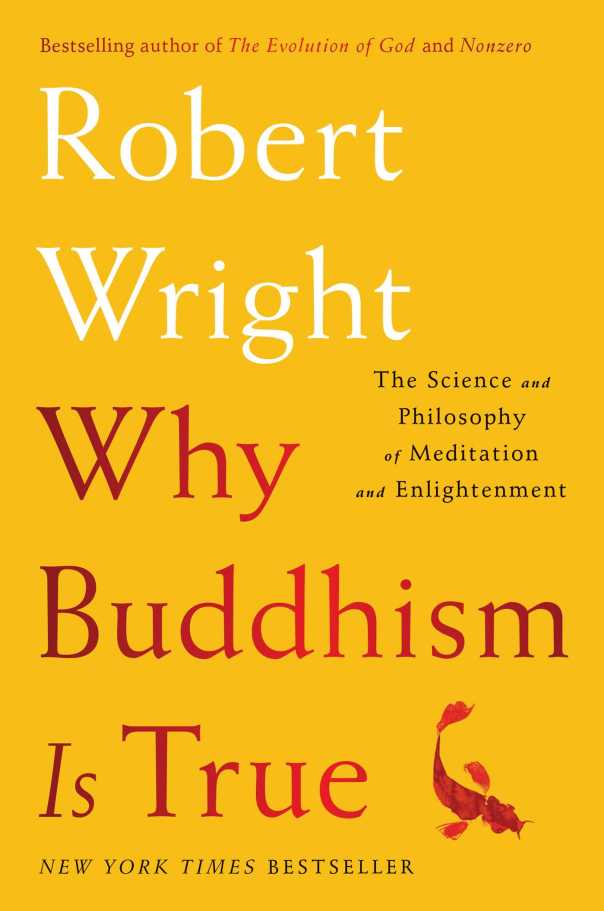

Why Buddhism is True – Bite Size

In case the Very Bad Wizards aren’t really your style, I’ve noticed that the Philosophy Bites podcast also have an interview with Robert Wright, focussing on some of the ideas he puts forward in Why Buddhism is True.

The first podcast I listened to with any degree of regularity, Philosophy Bites does a good job at presenting genuinely thorough takes on philosophical topics in a quick and accessible manner, and this ep is no different. They touch on a number of the important parts of text, with Wright doing likely a much better job than I at explicating the commonalities between modern-day psychology and Buddhist approaches to the human mind. They also discuss how these Buddhist ideas influenced other philosophers, particularly Schopenhauer, and the reasons why the apparent opposition of Buddhism-as-a-religion to the direction Wright wants to take it dissolve when you go back to the canon. Most satisfyingly, they explore some of the worries about how the Buddhist project, taken to its metaphysical extreme, might not sit especially well with the modern secular one, and why these can largely be put aside.

Philosophy Bites has been running for yonks now, and the back catalogue has plenty of interesting snippets from all over the discipline with big name guests and experts in the field. I recommend you check them out if you’re interested in intelligent conversation, in digestible portions.

Veganuary ’19 – First Bout

Welcome back to Veganuary!

In some ways, it feels surprising that we’re here again so quickly. In other respects (political, mostly), 2018 felt like it lasted an eternity. Hope you all had an enjoyable holiday period and that your celebrations weren’t too…disruptive. Weirdly, I myself didn’t have much of an appetite yesterday, so I’ll skip right ahead to today’s efforts!

Eased in to things with an old standard from yesteryear for tonight’s supper, the vegan lasagne with tahineh and garlic sauce.

Changing it up slightly from preparations past, I included some vegan No Bull ‘mince,’ which is mostly soy. We’d tried the No Bull burgers several times over the last year and found them pretty reasonable, so jumped at the chance for a guaranteed-vegan mince substitute – unfortunately, you have to go out of your way to make sure Quorn is properly vegan, as the standard variety is made with egg. After the slightest of investigations, it seems that No Bull is a proprietary brand of Iceland (the shop, not the country), with the manufacture being done in France – vaunted British industry strikes again! Taking back control! Having not eaten beef in more than a decade now, I’m probably not best placed to comment, but I wouldn’t say that the No Bull products approximate the flavour of meat especially well – which may or may not be a drawback for you. As was, it’s nice to have some variety in the protein source, regardless of whether it ‘meats’ the standard. I used about a third of the package for the lasagne.

For dessert and more general snacking needs, my wife has prepared some banana bread. For a while, now, we’ve found it’s easier to get a consistent bake by resorting to a muffin tray rather than a loaf pan when it comes to banana bread – too wet while simultaneously being too dense to cook all the way through without singeing the edges. As you can see below, we’ve picked up a rather quirky tray recently, and put it to good effect here.

The recipe itself isn’t anything particularly unusual – a standard chocolate chip banana bread recipe with a few tweaks to make it properly vegan.

The original ingredients –

2 cups all-purpose flour

1 cup sugar

1 teaspoon baking powder

1 teaspoon salt

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

3 bananas

1/2 cup butter (or the same amount of applesauce)

2 eggs

1 cup Chocolate Chips

Swap out the butter for applesauce as indicated, and replace the chocolate chips with fruit of your choice. We elected for some assorted citrus, and it really shines. As for the eggs, aqua faba (chick pea water) at a ratio of 3 tbsp to 1 egg works a treat.

The original recipe calls for between 40 and 50 minutes at 350 Fahrenheit, but this may need some adjustment downwards if you’ve gone for a smaller container, as we did. Think this was about 25 minutes.

And that’s that for today! I don’t know that I’ll be posting as regularly as I did last year, no need to retread old ground, but whenever I come across something new and worth sharing, I may throw something together.

Happy veganing!

Alternate Metta Meditation

Alternate Metta Meditation

Of the various fine-tunings that came out of the second portion of my meditation course with the local Triratna group, one of the most important was the distinction between active effort and being receptive, and finding the appropriate balance between the two. Active effort during meditation can be thought of as the focus we bring to bear on the subject of our meditation, whether it be the breath or the fostering of good feelings. Receptivity, by comparison, is the ability to remain open to and recognise the experience we are having in the moment. It’s possible to stray too far towards one at the cost of the other – keeping yourself so clamped down on one element of the meditation that it becomes a source of stress, or being so relaxed in your approach that receptivity becomes passivity. When put that way, the importance of having these two in balance is self evident, but it can be more difficult to realise that in the moment, or if you’ve not really considered them as the complementary features of a good meditation that they are.

By way of illustrating the importance of receptivity, our group leader presented a different spin on the metta bhavana meditation that I’d detailed previously. As you may recall, Metta Bhavana is not my preferred meditation style, but I do find this alternative approach to be rather better than the first.

Unlike the other version, which was broken down into many distinct phases, this alternate really only has two halves.

Nurturing the Self

The first is almost entirely receptive. You ease into your experience, taking note of the space around you, perhaps doing a body scan to open up your sense of your own physicality. Pay attention to the sounds of your environment. Turn your focus inwards, on your own emotional state without trying to judge it or change it – just taking note, recognising that, today, this is where you are working from.

Take note of any physical pain or discomfort you might be in. If you can, reposition yourself to alleviate it, but, if you can’t, simply observe it. Take an interest in the sensation, without allowing it to become in some way overwhelming, the sole element in your conceptual space. Try to come at it with a genial curiosity, rather than a despairing exasperation. Counter-balance this with recognition of what is already alright.

Recognise that so much of what we do is motivated by a desire to achieve well-being, peace, joy, or a state free from suffering. See that in your current behaviour, and try to connect with this healthy, entirely natural desire.

Do your best to relax.

Connecting with Others

Once we’ve gotten ourselves closer to the a place of relaxation, the idea is to begin to imagine ourselves in a place of natural beauty. A seashore was the example put forward as standard, but, having little experience with them myself, I usually elect for something like seeing the night sky above the Georgian Bay, where you can still see the wash of the Milky Way in all its glory, or, alternatively, looking out over Lac Léman from above Lausanne at dusk, catching hints of Geneva at the far side from it’s electric penumbra. Go with what works for you.

Once you’ve built up this image before you, try to experience some of the awe you know it instils. Open yourself to this. You don’t have to go all the way to a Kantian sublime – being dwarfed by what you see – but it’s no bad thing to feel yourself humbled by it.

Once you’ve achieved this – simply relax into it. No need to actively pursue metta, just open yourself up to whatever you might have naturally present already. If it is beneficial, recognise the fact that, somewhere else in the world, there are hundreds if not thousands of people opening themselves to metta at the same time, all, invariably, wishing you well in turn. This isn’t just your own project your involved with, here.

From what our group leader was saying, this is apparently closer to the way the Buddha initially described as best to foster metta, to simply open ourselves to it and assist its growth. Whether that is accurate or not, it does side-step any issues you might have well-wishing individuals you aren’t especially keen on, or falling prey to distracting thoughts about the people you’re focussing on more broadly. All I know is, this is the one I turn to when I feel like I’ve got a deficit of positivity for others. You’ll have to ask them if it’s working!

Why Buddhism Is True – A Review

As I’d mentioned awhile back, one of the works that finally got me to commit to a multi-week meditation course was American Robert Wright’s recent Why Buddhism Is True, which I first heard about on the Very Bad Wizards podcast (something that’s worth checking out, just for itself). It’s the first work by Wright I’d encountered, but I’ve since come across more journalistic pieces that I’ve enjoyed, more within the realm he has carved out for himself. In case this is the first you’re hearing about him, as well, Robert Wright has become something of a champion of evolutionary psych, with book-length works such as The Moral Animal: Evolutionary Psychology and Everyday Life and The Evolution of God and plenty of shorter works.

In that vein, then, Why Buddhism looks at the overlap between the modern understanding of how the mind works and the Buddhist position, with particular emphasis on the modular theory of mind. I’m a believer in the modest proposition that past societies were not complete idiots and do have something to offer us, devoid of SCIENCEtm though they may have been, but it is still surprising just how well the Buddhist tradition syncs with this approach. And it’s not as if this was by design – insofar as I recall, Jerry Fodor wasn’t basing his modularity theory off a Buddhist psychology, and a quick scan of the Stanford Encyclopaedia does nothing to amend that.

Wright brings to bear a conservative evolutionary psychology on the issue, by which I mean he presents our psychology as being constructed by evolution, without importing any normative claims about our own behaviour or that of society’s on the back of it. Our mind, in this situation, is built up of modules that have been developed over hundreds of generation – all of which have been selected for based upon their effectiveness in continuing the genetic code they carry/arise from. Because of this, our mind, the feelings we feel, the intuitions that seem to just come about of themselves, are not necessarily oriented towards apprehending the world accurately or truthfully, especially when it would be more expedient to believe a fiction. This tendency to interpret the world inaccurately gives rise to all manner of problems on the macro level, and, on the more personal, huge swathes of time wasted in unnecessary frustration and misery. It also goes some way to supporting and explaining the Buddhist concept of dukka, the pendulum swing of life between the terrifying flight from the painful and the obsessive attachment to the fleetingly enjoyable.

All sounds pretty grim. Fortunately, by happy accident of our limited rationality, we seem to have a way to cut through some of the deception – mindfulness meditation. It’s almost enough to make you believe in the miraculous.

Why Buddhism is written from a fairly autobiographical perspective, with Wright sharing his own experiences, and struggles, with meditation whilst also unpacking some core Buddhist ideas, such as the “not-self” and the conception of “nothingness.” As he freely admits, his own attention span has always been pretty crap, so if he can learn to meditate and see the benefits in his life, just about anyone can. I found his approach – not necessarily overtly cynical, but healthily skeptical – somewhat close to my own, and so it was nice to have someone cast an appraising eye on some bold claims without coming at them as one already committed devoutly and still finding some traction. Lest you worry that terms like dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, domain-specific psychological mechanisms, or, on the other side, ‘the unconditioned,’ or ‘Vipassana,’ are all a bit boffin for you, keep in mind that Wright is first and foremost a journalist, and does a good job at situating the concepts, both scientific and Buddhist, he uses in his wider description. Indeed, the clarity and conversational tone of the prose is one of the book’s strengths.

Alongside the relating of his own experience, primarily focussed on intensive bouts of meditation on retreat and the strange and revelatory things that happen to him there, and the exploration of how (a) modern understanding of the human mind syncs with and supports that of the Buddhist approach, Wright also spends time discussing what some of the ramifications might be, should some core Buddhist ideas about the nature of the world actually turn out to be, you know, true. For this, he pulls in exegesis of Buddhist texts, weighing orthodox readings against some of the more radical, as well as the insights modern experimental psychologists and cognitive scientists have been accruing over the last century. Despite what could be some rather dry subject matter, none of this ever drags, enlivened as it is by a sense of real-world import. There are a few topics he brings up that hit particularly close to home for me, but I’m thinking that there is enough to go on there that I’ll spin it out into another post – as is, it’d be a strange shift in focus.

In summation, then, Robert Wright gives an account – personal, supported both by ancient tradition and cutting-edge science – as to how and why mindfulness meditation will likely improve your life. We need to recognise that we are creatures cobbled together through the vagaries of trial and error, and that, at no point, was this process oriented towards equipping us with an entirely truth-tracking apparatus nor indeed one that is focussed on our own happiness. The paradoxical statement ‘thoughts think themselves’ is shown to be true when we consider how the competing modules of our mind struggle against one another for conscious attention, seeming to foist themselves on ‘us’ almost out of nowhere. This leads to all manner of trouble, as these modules seldom if ever have what we would consider to be ‘our’ best interests at heart, and are inherently self-contradictory to boot. Even if this contradiction doesn’t rise to the level of intention, it still informs our actions from below (the unconscious belief “I’m the most important, which is why I’m allowed to act this way despite the law/social code/basic morality and no-one else is.” Only problem, everyone else feels this way, too – even if they are honestly, genuinely unaware of it). Fortunately, we can use meditation to reflect on these competing claims, motivations and feelings, and, with persistence, disavow them. “We” are not our thoughts, not our feelings, not the cacophony in our minds. We can hold them at arm’s length, stripping them of their immediacy and their power over us and rendering them, if not necessarily impotent, at least not something quite as overriding. It is a wonderful twist of fate that as we learn the truth about our existence, we simultaneously also find ourselves happier and generally just better, more compassionate people.

It’s Science. It’s also Buddhism.

Personal Practice – Little Rituals

Personal Practice – Little Rituals

The second portion of my course with the Triratna group here in Cambridge came to an end last week. Though there have been some things in my life that have prevented me from writing as regularly as I would have liked (almost entirely positive, never fear), I’ve been pretty good at keeping the daily practice going – whether getting a full session in in the morning, as I would prefer, or doing a catch-up in the evening. Part of what has kept me going is the subject of this post, the ways of separating your meditation time from ‘regular’ time, and thus heightening the importance thereof.

In this instance, something like ‘ritual’ becomes important. Which is not to say that there is some quasi-mystical affair at hand, but, rather, a set of regular behaviours, brought to bear in a way that mutually support and strengthen one another. This is more about positioning your own intentionality in a fruitful way than anything else, reminding yourself on a subconscious level what you hope to achieve with the session and your practice over-all, and putting yourself in a better space to achieve this. Ultimately, what you find works for you is the best course of action, but I can’t see any harm in relating my personal experience – take what bits you find most useful!

Transition – Setting Up

If you’ve tried meditating, you’ll know that what you experience during meditation, the focus and attention on things, is quite distinct from what you have going about your normal business. Part of getting our attention where it needs to be for meditation comes from those parts of a session like an initial body scan, drawing the mind to parts of the body and feelings that it might be less likely to to heed in regular life. Even before this, though, it can be helpful to put ourself in the right frame of mind by preparing our external space. I meditate in our office, so this often includes putting a sign on the door to let people know not to disturb me, throwing down the yoga mat and grabbing my stool and cushion, and, though not always, setting some incense alight. Going through these motions gives me a moment to reflect on what I’m about to launch into, as well as marking a boundary between whatever I was doing before and what I’ll be doing for the next half hour.

During the Meditation

Obviously, the primary focus at this stage is going to be the meditation itself, whatever you’ve elected to go for – mindfulness of breathing, metta bhavana, a guided meditation or something else. However, there are things you can do before that you can bring to mind to support yourself during, such as considering a work of poetry you then bring to mind later, or finding something in your immediate surroundings that instils some positive emotion. During one of our sessions at the Buddhist Centre, we were asked to select from a large assortment a postcard that spoke to us. We were then to bring the postcard home and place it somewhere close to where we meditate – as a visual link between what we were trying to achieve overall, and the benefit of having a group experience and access to the calming space at the centre itself. This is the one I picked –

It shows a detail of a work called Pilgrims on the slopes of Mount Fuji by Shibata Zeshin, from 1880. It’s a nice image in and of itself, and obviously topical, but I thought the scene it evokes to be a useful reminder when it comes to meditation more broadly. We’re all trying to climb the mountain, whether it be towards a more equanimous perspective or enlightenment full-stop. However, the way up isn’t a straight line – it’s going to involve cutbacks, dead ends, and a struggle, which is well expressed by the zig-zag line of the pilgrims. Also, some people will be higher up the climb than we are, and there are some people who are better positioned to lead the way up than we might be ourselves. The trick is to not get frustrated by momentary setbacks, bad sessions or lapses in practice, but to keep on climbing. Not a bad thought to have when we might be struggling.

Transition – Setting Down

Coming out of a meditation session can be something of a startling experience, so it’s best not to make it too abrupt if it can be avoided. I know that leaving a buffer of ten minutes or so between my scheduled finish time and whatever I have to get myself on to next is beneficial. There was a period where I was experiencing a relatively ragged finish to the session, with the last stage or portion subjected to mounting anxiety or distraction as I was thinking about the immediate future, so leaving myself a small portion of time has been a good idea.

Quite a few of the sangha members at the Buddhist Centre would finish their meditation with an obeisance towards the shrine in the room. Obviously, this isn’t especially appropriate if you’re self-conscious about that sort of thing, or if you’re just in it for secular reasons, which is sort of where I’m coming from. However, the way our group leader explained her own position is hard to find fault with. The action, while signalling an end to the meditation itself, is less about submitting in some way to the Buddha, or to the statue you see before you, than it is a salute to the intention behind the meditative practice overall, a recognition of what is trying to be achieved.

Another thing I do in closing off my session is to take some time to reflect on how it’s gone. Every week during the program we would be given a sheet with space to write about that day’s meditation, as well as useful tips or aspects to focus on for that particular session. Though this was useful, I found the space somewhat limited, with only a line or two allowed for each day. Back in October, I started keeping more detailed records in a converted diary I had lying around. It’s already laid out in a daily format, which is great to provide for a single session, but it has more space than the previous multi-day affair. Taking a few moments immediately afterwards allows me to put down while still fresh any particular struggles or successes I may have experienced, and keeping a record allows me to notice commonalities between sessions and subtle ways I’m improving that I might otherwise miss.