Monthly Archives: April 2016

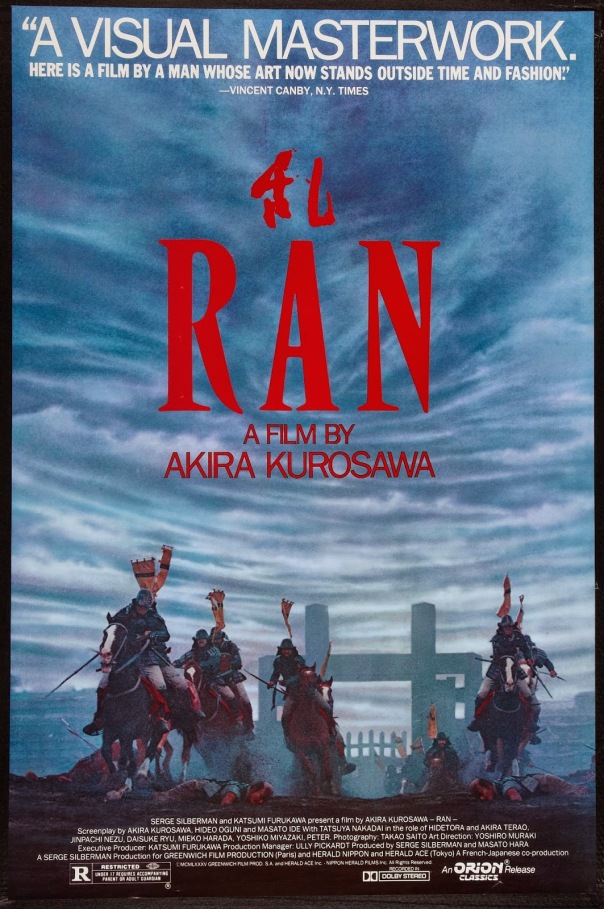

Ran

Ran

If you’ve been in Britain over the last couple weeks, there’s little doubt you’ll be aware of the fact that last Saturday was the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s demise. It’s spread beyond our shores, too – seems like everyone in the Anglophone literary world is making hay with this one, whether it be the New York Review tracking his post-mortem uptake, the CBC ginning up attention for goings-on in the Colonies, or LitHub valiantly trying to refocus some of the fervour on his under-appreciated contemporaries. I suppose, then, that this will be my addition to this metastasising glut.

Along with the articles, the radio works, the festivals on offer around the country, the British Film Institute is running several ongoing screenings – both filmic versions of the plays done straight and adaptations of the works in more of a vernacular vein. More to the point, I caught a showing of Akira Kurosawa’s 1985 epic Ran Sunday night. Unfortunately, though there are plenty of other films yet to come in the series, Sunday was the end of the run for Ran and this is definitely one you want to catch on the big screen.

Ran, which loosely translates as ‘Chaos’, is a combination of Shakespeare’s King Lear and the Japanese legends surrounding daimyo Mōri Motonari. Accordingly, the structure and characterisation is loose, the largest difference coming with Lear’s three daughters gender swapped for sons. This allows Kurosawa to examine the familial relations of feudal Japan, as well as the violent, predatory society the story draws from. Ran wasn’t Kurosawa’s first stab at Shakespeare – back in ’57 he wrote and directed Throne of Blood, an adaptation of la Pièce Écossaise, to near universal critical acclaim. It’s worth noting, outside of England, some of the largest Shakespeare companies are in Japan – fertile place for the high drama and comedic spin exhibited by so many of Shake’s works.

Pulling from Lear, Ran’s overarching plot should be little surprise to those current with the play – a patriarch, tired of the rigours of rule, divides his realm between his three offspring. The eldest two fall over themselves in obeisance, while the third stands aloof, seemingly harsh in their contempt. The patriarch banishes this youngest child, alongside a doughty servant. It quickly becomes clear that the first two children were false in the love they expressed; spurred by greed and jealousy, they start on a path that leads to the ruination of the family as a whole.

Unlike the original play, though, the world of the film is, true to its namesake, malevolent in character. Lear was foolish, to be sure, but Hidetora, the Patriarch-figure of Ran, earns what he has coming by way of past deeds. A fierce warlord who won his land through conquest, his previous actions – the blinding of children, the marriage of conquered enemies’ daughters to his own sons, the well-deserved reputation of brutality – sowed his own downfall. If the world of King Lear was uncaring to human suffering, the world of Ran delights in it. Elsewhere, I’ve read it described as Hobbesian, and the characterisation rings true for me. This is lampshaded early in the film, Hidetora’s true son, Saburo, calls him a fool for trusting in himself and his brothers when the world is so bloody and rough. They can’t but turn on one another. With Nature so designed, there is no need for a character the equivalent of Edmund to stir up chaos and bloodshed, it was foregone from the start. For all that, Lady Kaede, the wife of Hidetora’s eldest and, after Hidetora, the most lavishly dramatic of the characters, is possessed of a downright Machiavellian bent – much to the detriment of all others.

With Ran, a battery of the best qualities of film are brought to the fore – the strength of the piece is in its harnessing of the spectacle. Vibrant colours, sharp incongruencies in sound, juxtaposition of multiply angled scene cuts and broad tracking shots that simply aren’t possible on stage. Music is used effectively: a combination of traditional Japanese shakuhachi for heightened emotion and a girthy Mahlerian, late-Romantic score for lengthier passages. There is a scene, a pivotal battle, where all diegetic sound fades and we are left with merely the images and the music – a haunting juxtaposition that lends a dreamlike quality to the proceedings. The viewer is lulled into calm as the violent imagery passes before the eye, only to be brought forcibly back into the action with the crack of a gunshot and the murder of a key character.

In spite of all this, I found the presentation, at least in comparison with the source material, to be opaque. A beautiful spectacle, uncompromising in its presence, concrete, and direct. My initial thought is that this might be resultant of a combination of the Noh tradition the film draws upon, which primarily used movement to express emotion, and the necessary limitations of watching a film in subtitles. There’s only so much that can be expressed by translated words alone, and, given the broadstroke emotions that Noh is renowned for, I was left feeling as if, at least for the foreign viewer, what we get is all surface – beautiful surface – but surface nonetheless. Don’t go into this one anticipating the passionate intimacy that’s idiomatic of Will’s best poetry, intricate soliloquies that bare the soul of the speaker, nor the more subtle play of emotions that’s possible with film, the benefit of viewing the actor from a distance of bare inches as the cast of conflicting emotions that play across the face tell more than words ever could – you’ll get neither.

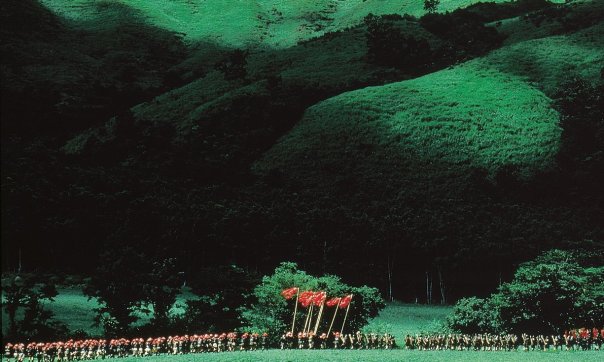

The surface here, though, is well worth the price of admission. The aforementioned tracking shots are something to behold – 1400 extras were hired for the film, and the synchronised movements of masses of people, the cavalry formations, the sheer scope of it is stunning. The film would go on to win the Academy Award for costume design, and it is well deserved. Much of the film was shot on location, in areas around Mt Aso and the historical castles of Himeji and Kumamoto, and the landscape is as much a character as any of the actors.

This castle was built, full scale, with the sole intention of burning it down. Dedication to detail.

There is a punchiness in the effects, the stunts, that is sadly lacking in these latter days of CGI – when you see someone take a fall from a horse, and watch them scuff along the dirt, you know that it hurt – when they get clipped by a hoof, you know that it’ll bruise. The immediacy of running out of a multi-storey building that is literally burning down around you can’t be mimicked by greenscreen. Out of restriction comes creativity, and, when you can only manage one take before the whole scene burns up, you get something real.

If ever you get the chance to catch Ran in theatres, I highly recommend it – it certainly takes liberties with the Shakespearean source material, but produces something equally good. As the final scene winds up, the figure of a blind man lost and alone, standing above a ruined castle and backlit by the setting sun, you are given a sense of the folly of life, stripped of any comforting pathos.

In the interim, though, the BFI is still running a bunch of Shakespeare-themed films. Get down to London and see ‘em!