Category Archives: Reviews

Post-prandial ruminations.

Why Buddhism Is True – A Review

As I’d mentioned awhile back, one of the works that finally got me to commit to a multi-week meditation course was American Robert Wright’s recent Why Buddhism Is True, which I first heard about on the Very Bad Wizards podcast (something that’s worth checking out, just for itself). It’s the first work by Wright I’d encountered, but I’ve since come across more journalistic pieces that I’ve enjoyed, more within the realm he has carved out for himself. In case this is the first you’re hearing about him, as well, Robert Wright has become something of a champion of evolutionary psych, with book-length works such as The Moral Animal: Evolutionary Psychology and Everyday Life and The Evolution of God and plenty of shorter works.

In that vein, then, Why Buddhism looks at the overlap between the modern understanding of how the mind works and the Buddhist position, with particular emphasis on the modular theory of mind. I’m a believer in the modest proposition that past societies were not complete idiots and do have something to offer us, devoid of SCIENCEtm though they may have been, but it is still surprising just how well the Buddhist tradition syncs with this approach. And it’s not as if this was by design – insofar as I recall, Jerry Fodor wasn’t basing his modularity theory off a Buddhist psychology, and a quick scan of the Stanford Encyclopaedia does nothing to amend that.

Wright brings to bear a conservative evolutionary psychology on the issue, by which I mean he presents our psychology as being constructed by evolution, without importing any normative claims about our own behaviour or that of society’s on the back of it. Our mind, in this situation, is built up of modules that have been developed over hundreds of generation – all of which have been selected for based upon their effectiveness in continuing the genetic code they carry/arise from. Because of this, our mind, the feelings we feel, the intuitions that seem to just come about of themselves, are not necessarily oriented towards apprehending the world accurately or truthfully, especially when it would be more expedient to believe a fiction. This tendency to interpret the world inaccurately gives rise to all manner of problems on the macro level, and, on the more personal, huge swathes of time wasted in unnecessary frustration and misery. It also goes some way to supporting and explaining the Buddhist concept of dukka, the pendulum swing of life between the terrifying flight from the painful and the obsessive attachment to the fleetingly enjoyable.

All sounds pretty grim. Fortunately, by happy accident of our limited rationality, we seem to have a way to cut through some of the deception – mindfulness meditation. It’s almost enough to make you believe in the miraculous.

Why Buddhism is written from a fairly autobiographical perspective, with Wright sharing his own experiences, and struggles, with meditation whilst also unpacking some core Buddhist ideas, such as the “not-self” and the conception of “nothingness.” As he freely admits, his own attention span has always been pretty crap, so if he can learn to meditate and see the benefits in his life, just about anyone can. I found his approach – not necessarily overtly cynical, but healthily skeptical – somewhat close to my own, and so it was nice to have someone cast an appraising eye on some bold claims without coming at them as one already committed devoutly and still finding some traction. Lest you worry that terms like dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, domain-specific psychological mechanisms, or, on the other side, ‘the unconditioned,’ or ‘Vipassana,’ are all a bit boffin for you, keep in mind that Wright is first and foremost a journalist, and does a good job at situating the concepts, both scientific and Buddhist, he uses in his wider description. Indeed, the clarity and conversational tone of the prose is one of the book’s strengths.

Alongside the relating of his own experience, primarily focussed on intensive bouts of meditation on retreat and the strange and revelatory things that happen to him there, and the exploration of how (a) modern understanding of the human mind syncs with and supports that of the Buddhist approach, Wright also spends time discussing what some of the ramifications might be, should some core Buddhist ideas about the nature of the world actually turn out to be, you know, true. For this, he pulls in exegesis of Buddhist texts, weighing orthodox readings against some of the more radical, as well as the insights modern experimental psychologists and cognitive scientists have been accruing over the last century. Despite what could be some rather dry subject matter, none of this ever drags, enlivened as it is by a sense of real-world import. There are a few topics he brings up that hit particularly close to home for me, but I’m thinking that there is enough to go on there that I’ll spin it out into another post – as is, it’d be a strange shift in focus.

In summation, then, Robert Wright gives an account – personal, supported both by ancient tradition and cutting-edge science – as to how and why mindfulness meditation will likely improve your life. We need to recognise that we are creatures cobbled together through the vagaries of trial and error, and that, at no point, was this process oriented towards equipping us with an entirely truth-tracking apparatus nor indeed one that is focussed on our own happiness. The paradoxical statement ‘thoughts think themselves’ is shown to be true when we consider how the competing modules of our mind struggle against one another for conscious attention, seeming to foist themselves on ‘us’ almost out of nowhere. This leads to all manner of trouble, as these modules seldom if ever have what we would consider to be ‘our’ best interests at heart, and are inherently self-contradictory to boot. Even if this contradiction doesn’t rise to the level of intention, it still informs our actions from below (the unconscious belief “I’m the most important, which is why I’m allowed to act this way despite the law/social code/basic morality and no-one else is.” Only problem, everyone else feels this way, too – even if they are honestly, genuinely unaware of it). Fortunately, we can use meditation to reflect on these competing claims, motivations and feelings, and, with persistence, disavow them. “We” are not our thoughts, not our feelings, not the cacophony in our minds. We can hold them at arm’s length, stripping them of their immediacy and their power over us and rendering them, if not necessarily impotent, at least not something quite as overriding. It is a wonderful twist of fate that as we learn the truth about our existence, we simultaneously also find ourselves happier and generally just better, more compassionate people.

It’s Science. It’s also Buddhism.

Getting Theroux to the Truth about Polyamory

Getting Theroux to the Truth about Polyamory

Documentarian Supreme and Unlikely Male Sex Symbol Louis Theroux has a new series out on BBC 2 called ‘Altered States’, and we caught the first ep last week – Love Without Limits.

Polyamory is a weird one. Straight dude, happily settled in a monogamous marriage, it’s not something that’s really on my personal radar, though I discuss the concept fairly often with my wife and I’ve a few friends/acquaintances that lean that way. Trying to keep up with the kids, I guess.

We, my wife and I, are generally agreed that there’s nothing wrong with it in principle – though we’re married, we don’t hold any great stock in the so-called sanctity of marriage (it’s an economic pact for goats, land and healthcare coverage, people) – but we can’t help but feel that the execution is where things get messy. Having never done anything like it, it seems like it’d require a group of exceedingly mature individuals to come off successfully, navigating the thorny emotional maze of jealousy, possessiveness, respect, dignity and what all else. To steal my wife’s insight, there’s something inherently late-stage capitalist about the whole thing, as if the transactional nature of time sharing couldn’t have come about without the assistance of Google Calendar or the like. On top of that, though my sample size is exceeding insufficient, it seems like people who opt for it as a lifestyle really aren’t the best, most well-rounded candidates to begin with. However, it’s not like any relationship – straight, gay, monogamous or open – is a walk in the park. All require heaps of effort if they’re going to be successful, and all are going to have their rough patches. Also, everyone always-already comes equipped with baggage. We’re all broken sacks of crap, so it’s not like polycules are going to be any more fucked than binary relationships, really. And so, I remain ambivalent. Did the documentary do anything to change my mind? Let’s find out!

In order to find a viable pool of candidates for investigation, our intrepid Louis travels to that mecca of American alt-liberalism, Portland, OR (because, of course). There, he focusses in on three groups of self-described poly-people: one set of more (temporally) mature individuals, somewhere in their late-40’s early-50’s, one ‘throuple’ – a combi affair of two men and one woman, and one swirling mess of millenials, all co-habitating under one roof, with a baby on the way. He spends time interviewing them individually and in groups, posing questions aimed at unpacking the situation for all of us normies who aren’t quite hip to it, as well as joining them for meals and social events, showing what their lives look like on something approximating an average day. If you’ve seen any of Theroux’s previous work (have you been living under a rock?), you’ll know how skilfully he inserts himself into situations like these – he’s got a fantastic aptitude for putting people at ease and generally avoiding offence while still putting hard, intimate questions to them, and this doco is no different.

So, with the answers he teases out, do I feel any differently about polyamory? Not really, I’m afraid to say. In each instance, it seemed as if there was either active abuse/advantage being taken, or an otherwise gross imbalance in power/attention.

The first set I mentioned, the older ones, are, on the face of it, two distinct nuclear families, living separate lives – two parents, multiple kids. However, the wife of family 1 and the husband of family 2 are, additionally, in a relationship. Wife of family 2 is…visibly irate with her husband, though she says that their marriage is troubled due to other reasons, and she supports the poly affair. So long as she is able to moderate it to her tastes.

Husband of family 1 is adamant that he is a poly individual as well, despite never having been in a relationship outside the one with his wife since they began their poly lifestyle…a full decade ago. Thou dost protest too much, mate. I actually felt rather sorry for him in a few scenes – his wife is quite domineering, and it’s difficult to take anything away from what’s seen other than that he is on the losing end.

Meanwhile, Wife 1 and Husband 2 carry on as if they’re a bunch of hormonal teens.

What about the Throuple? Everyone is equally involved here, right? Unsurprisingly, that’s complicated.

The two men are in a relationship with the woman, so it looks a bit like a water molecule, if you like. I think there might be hydrogen peroxide joke in here somewhere, but I can’t quite wrangle it. Suffice it to say, the stable water molecule affair was not the original configuration. And not everyone seems to self-describe in the same way. To hear the original guy call it, he counts himself as monogamous, but it just happens to be that the person he is monogamous with is poly. The woman describes her history of anxiety and depression (and lets be real here, who hasn’t got some of that going?) and it seems like the effort by both guys is to try and assist her needs. Or, at least it would be, if we heard more than 12 words from guy 2 in the whole doco – he’s always in-scene, just keeping mum.

So, what about our final group? Surely they’re alright?

As I’d mentioned, one of the group is pregnant, and this is going to understandably put a strain on any relationship. The woman who is pregnant had earlier mentioned that she’d been burned in a poly relationship previously – married, only to have her husband nicked by their mutual, female, partner. Which absolutely sucks.

But it also just adds to the mystery as to why she’d pick now – fit to burst – to take on a new male partner. In one-on-one interviews, you can see that her baby-daddy, as much as he puts on a brave face, is struggling with it. He does, of course, say that this is part of being poly, that you can’t expect to have control or privileged access to another person, which is commendable (and a good standard in any relationship – consent is important folks), but, the bigger question, why choose now to start a relationship? It strikes me as disrespectful, not wantonly so, but by way of negligence. And, get ready to have no time with your new squeeze when the kid arrives, unless you bung all rearing duties on baby-daddy, which would be even worse. I don’t know – perhaps this is just my decrepit monogamist brain failing to get it.

It’s worth pointing out that, quality as Theroux may be, he’s still here making a product, for a specific audience. When the status quo is set, and your audience is of said status quo, the way you cut your documentary is going to lean in a very particular way. While the situation as presented on-screen definitely tells one story, we as the viewer have little access to the way in which it was edited, little access to what the broader circumstances may be. There’s always going to be a salacious angle to a topic like this, and seeing things go a bit sour adds a frisson of drama. Much like the recent, very well-crafted adaptation of Wanderlust, I can’t help but wonder if this whole thing was slanted from the start, designed to appeal to semi-conscious biases of those just liberal enough to take an interest, but still, secretly, disapproving.

A good remedy for this might be a documentary created with the same amount of craft as shown here, but by someone who is poly themselves. Not a hagiography, but something that takes into account the peculiar struggles whilst also truthfully displaying the positives that an outsider might miss. If something of the sort does exist, please let me know.

As ever, check it out for yourself, make your own mind up.

Also, check this out, because it is so friggin on-point. Chris Fleming is a modern prophet.

A Return to Osten Ard: Tad Williams’ The Heart of what was Lost and The Witchwood Crown

As I mentioned previously, there was another series that I had returned to recently to provide a nostalgia fix. Unlike Barbara Hambly’s Darwath trilogy, though, which saw me rereading the original works, it’s been all fresh with Tad Williams’ latest series, The Last King of Osten Ard. The original series of Memory, Sorrow and Thorn (consisting of a trilogy of books – The Dragonbone Chair (1988), Stone of Farewell (1990), and To Green Angel Tower (1993), though the final was split in two for resale purposes) won Williams a well-deserved place amongst the fantasy greats and paved the road later heavy hitters such as The Wheel of Time and A Song of Ice and Fire. I’m pleased to say that the first offerings of this latest series have not let down the source material.

The Heart of what was Lost

Williams is nothing if not ambitious with this return to Osten Ard. Beyond the intended trilogy of full-length novels (and these are long books – ain’t called epic fantasy for nothing!), he plans to write two novellas to fit between the other works. The first of these, The Heart of what was Lost, came out before the first full book and acts as a bridge between the original and the new.

Picking up almost directly from the closing of To Green Angel Tower, The Heart does a good job at reminding the reader of the main characters, lands and history of Memory, Sorrow and Thorn, while also trying out something fresh. The novella is actually really the story of a single battle, a mopping up by the human victors of the original series as the try to put to bed any chance of a resurgent Hikeda’ya troubling generations to come. If only they were so lucky.

We join Duke Isgrimnur and a sizeable force on the march north, travelling into lands still gripped by the former Storm King’s power – icy winter still blasting the Frostmarch and Rimmersgard, even late into the year. They chase the scattered remains of the Norn army – those Hikeda’ya and Tinukeda’ya who didn’t perish at the battle of the Hayholt. Inevitably, Isrimnur’s men lay siege to Sturmspeik itself, the last fastness of the Norns.

In a break with the earlier works, much of this story is from the point of view of Hikeda’ya, giving the reader insight into their culture and daily life in the subterranean city of Nakkiga. This does good work at fleshing out things only hinted at in the initial trilogy, which will be an important springboard for The Witchwood Crown, the first full novel of the The Last King series. New characters are introduced who will have roles to play in the novels to come, and there is a satisfying bit of pathos built up over the course of the work. The focus is tight, but there are some untelegraphed twists that hook in nicely to the larger story. All in all, an unusually lean offering, but one that whets the appetite for more!

The Witchwood Crown

The Witchwood Crown sees us back on familiar ground in terms of scope – we’re returned once more to the sprawling high fantasy of the original books.

King Seoman and Queen Miriamele are travelling, with full entourage, to Rimmersgard. Three decades have passed since the events of The Heart and Isgrimnur is an aged man, his once-mighty physique wasted away, leaving him on his very deathbed. The train make haste to the North, but, for political reasons, must make a detour to Hernystir in the West on their way. It is true that Seoman (still Simon, to his friends) and Miriamele rule all the lands of Osten Ard under the High Ward, but the client kings of the various states can be unruly, personal pride and expedience overriding allegiances to far-off Erkynland. True to his young self, Simon has little stomach for politicking, and it is a good thing that Miriamele, sole child of Elias, the Mad King, was reared for courtly life. Sometimes subordinates need a strong hand to remind them who truly rules.

It is during these travels that we are brought up to speed on the changed situation for the joint Monarchs and the whole of their Realm – their son, the prince John Josua, died some time ago –carried off by a fever that swept through the Ward. Luckily, he left two heirs, Princess Lillia and Prince Morgan. Unluckily, Morgan, the elder of the two, is a rake – interested in little other than wine, women and dice, he is a poor imitation of his virtuous, studious father, and certainly unfit to inherit the crown. Both monarchs have been devastated by the death of their son, which Williams is…very…keen…to tell you! If Barbara Hambly was intent on informing you Gil was a scholar, Tad is desperate for you to get just HOW DEVASTATED Seoman and Miriamele are. Perhaps I’m being unfair, and the death of child, something I’ve never even come close to experiencing, can leave parents with the degree of ptsd evidenced throughout the story, but it honestly got a bit tiresome. One of the more unfortunate aspects of the book, to my mind. At any rate, the clashes between generations are a recurring motif, as each party secretly recognises the right way forward, but, through stubbornness or self-pity, allows the situation to stagnate. It’s certainly frustrating for the reader at times, but, just as I was saying with Hambly’s approach, this is what sets the work apart. The characters are flawed, and better for it.

Meanwhile, in Nakkiga under Sturmspeik, dark things are stirring. Hikeda’ya society has changed radically after the events of The Heart, the near-sacking of the city showing the Norns that they would have to give up on many of the old ways if they were to survive in the world. But Queen Utuk’ku is finally awakening from her multi-decadal slumber, the somnolence between death and life she was cast into following the disaster at Asu’a, and there is every likelihood that she will denounce the changes, the desecrations, made in her absence. With her god-like control of the Hikeda’ya, Great Houses are known to fall at even the hint of her displeasure. Amidst this scene of tumult, a party of elite warriors are sent forth from the mountain, their mission fell and secret even to most of their number. On the edges of Norn lands they are joined by a Black Rimmersman, one of the Queen’s mortal slave-catchers – purportedly to guide them, but with motivations all his own.

The individual narrative threads soon tangle into the skein that is the hallmark of these high fantasy tomes – characters haring off to the four corners of the map on seemingly unrelated quests that you can be sure a writer of Williams’ skill will pull together in the end. The close of The Witchwood Crown sets up the next novel on several fronts: new quests are just beginning to be undertaken, a genuine threat is declared from a corner long teased at, dark political intrigue blooms from an unexpected source (this one was a bit of a gut-punch, even if -some of it- was satisfying), and the right number of secrets are revealed to keep you wanting more.

I wouldn’t say that it punches at the same weight as something like the Malazan series (the review of which, incidentally, continues to be the most heavily-trafficked of all my posts. Must have some superior SEO or something.), but that also grapples with material of a more obviously-adult nature, coupled with a more ambitious narrative style. All the same, this long-awaited return by Tad Williams scratches the right itch. If you’re a fan of the original batch, or you’re looking to fall into some epic fantasy for a few days (as one would hope, the book can read as a standalone. Appendices are supplied glossing the history of the previous books and various peoples and places referenced, for the uninitiated), I heartily recommend these new books from The Last King of Osten Ard.

Unfortunately we will have to wait until September to get our hands on Empire of Grass, the next instalment. No doubt it will be worth it!

Two Recent Psychology Works that Miss the Mark

Caught this article a few days back, and, whilst I mainly agree with the arguments made, there are some important counterpoints I think need to be voiced.

The piece in question is a ‘review’ of two recent books, both published by people within the world of professional psychology, trying to get to grips with the current malaise of American society. Neither of which I’ve read myself, so, I can’t comment in good faith beyond what is being reported. Review of a review – this blog brings the quality!

The first, The Dangerous Case of Donald Trump: 27 Psychiatrists and Mental Health Experts Assess a President, purports to be a cautionary statement regarding the current president, written by a collection of professionals. Importantly, they dodge falling foul of the Goldwater Rule – that unwritten law of the psychology community which prevents professionals from commenting on public figures whom they haven’t, themselves, examined – by saying that they are speaking not as practitioners, but as concerned citizens. As the article points out, if this is the case, that they are nothing more than another set of voices in a remarkably substantial torrent of commentary, do they deserve to be accorded any special status? Not really, especially when the main thrust of their argument is comprised of nebulous statements drawn from speciously broad tracts of ‘data’ or things that other people have already said elsewhere. This is little more than signal boosting, providing a veneer of professionalism (while carefully dodging even the commitment to that) to the standard, anti-Trump rhetoric we’ve been fed the past year and more. As I’ve mused before, this may have its instrumental use, but I’m hardly about to shell out for it. So much for that, then.

It’s the second book where I begin to depart from the article’s position. Rather than focussing so closely on a single character, such as the president, Twilight of American Sanity: A Psychiatrist Analyzes the Age of Trump. takes a look at American society more broadly. The author, Allen Frances, is a bigwhig of the evo-psych movement, and brings that “methodology” to bear in looking at the current state of Yankiedom. At least from what the article presents, this is classic evo-psych overreach – we have broad-stroke, un-nuanced generalisations based off a wonky understanding of evolution being used to try and explain events and trends best investigated by other disciplines. Frances seems to end up at a neo-Malthusian position – the real evil in our world is not gross gulf between classes, or the perfidious ideologies of racism or sexism – no, the genuine article driving all misery is over-population. From here, he jumps into a righteous indignation that so many women had the gall to not vote for Clinton, actively undermining the access they would have to prophylactics, thereby continuing to burden the planet with their undesired and undesireable offspring. I grow ever closer to the anti-natalist stance myself, but this line of argumentation is just silly. Repeating the tired adage that people owed their vote to HRC, because she was a woman, or the Dem candidate, or was possibly the lesser of two evils, is at best to misunderstand how democracy works. The tenacity with which a certain stripe of liberal grips this canard is indicative of the hubris that was such a large part of why Trump won the election (even with fewer votes – it’s a stupid system, but he still won). Clinton was ultimately found to be undeserving, and the condescending expectation that it would be otherwise played a big role in that.

Reading the article comes at a good time for me – I’ve been working my way through Robert Wright’s Why Buddhism is True – which is a book on how Buddhist practice, stripped of its more metaphysical trappings, syncs up quite nicely with the modular theory of mind. A lot of Wright’s explanations stem from evolutionary psychology – it’s what he’s famous for, after all – but the way in which he brings it to bear is importantly dissimilar from the abuses the field is so often used for. Rather than some lock-step, “society-is-this-way-today-because-we-were-this-way-100,000-years-ago-so-your-manager-deserves-to-make-more-money-than-you” is/ought nonsense, Wright marshals our evolutionary history in a much more conservative way. Rather than go for the strong, ‘everything we see today is precisely down to our evolved nature,’ Wright presents the weaker claim that our bodies, and hence our minds, are not really interested in the things we might deem important (like happiness, truth or personal flourishing) – rather, they are geared towards genetic proliferation, and will cut corners to get there. They’re all we’ve got, but they shouldn’t necessarily be trusted. And meditative practice, so the argument goes (as well as the evidence), is a good way of both identifying where we’re being lied to, and eventually overcoming it. This accords with my own views, so, this critical look at another use of evo-psych is a good reminder that I shouldn’t be allowing my own prejudices to give Wright’s ‘just-so’ stories a pass. In omnibus operandus premebantur!

But, all that doesn’t really detail my divorce from the article. Assuming the presentation of the two works is accurate, I generally agree with the criticisms made. It’s the closing statements where I take umbrage –

“What are psychiatrists good for, in the political sphere? On the evidence of these books, not much…A therapist can’t offer to give you more money, or literal freedom, but they can teach you to tolerate your lack of it without acting out. They can help you to function in society as it is. This is a crucial function, and what the books bring us: a bit of foresight, but not a diversion from our fate.”

While this statement may be true for far and away the majority of main stream psych, and certainly the pabulum offered up by these two books, I feel as if it is throwing the baby out with the proverbial bathwater to dismiss the whole discipline. For the past couple of years I’ve been thinking of going back to school to study psych, with the belief that, if answers are to be found anywhere as to why people continually vote against their own interests, why solidarity and class-action constantly founder, why people so often bow to their dishonourable, rapacious desires in the face of what they know to be just, then it must be at the intersection of psychology and sociology. And if those answers can be found, perhaps the way to overcome these failings can also be discovered.

Furthermore, I feel like teaching a patient to ‘tolerate [the] lack…without acting out’ is falling grossly short of the ideal. It’s true that much therapy does aim for this, in particular the novel fetish for ‘mindfulness’ in the workplace, whose proponents should be driven from our communities with pitchfork and torch like the monstrous class traitors they are. But the real goal should be the shoring up of the person, providing them the skills to surmount their situation, to better push back against it. Psychotherapy shouldn’t be perceived, nor practiced, as a rearguard action, but rather as the buttressing of a position to better sally forth from in the next battle.

Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson: Ben Swolo goes to the Emotional Side

Like a significant slice of the globe, we caught the latest Star Wars over the holiday break. It hit the right buttons at the time, for what is really just a kids action piece – we’ve fallen into a bit of a tradition with this third-wave Star Wars series along with another couple, one group picking up the tickets for everyone on a rotating basis, then having a bit of a gab afterwards. We all walked away from this one fairly pleased, and only on thinking it over afterwards did the more egregious issues surface, as is usually the way of these things.

Given the rather cut-and-dry characterisation in Star Wars VII, I was hoping (with little reason) that there would be more available for the actors in the next film. It was an improvement – the characters had been established, and the narrative hinged, even if rather clumsily, on presenting the possibility of a grey character in Kylo Ren. But, as is ever the case with the monomyth, VIII is a story told in broad strokes – not so much characters as archetypes.

Thus, on the nearer side of Christmas, we finally got around to watching Jim Jarmusch’s Paterson (2016), the story of a bus-driving poet named Paterson, from the city of Paterson, New Jersey. Given the subject matter and the possibilities hinted at in the trailer, I was more than interested. Thus far I’ve avoided watching Girls as a matter of principle, so I thought, here might be an example of the actor Adam Driver could be, in a work that was actually palatable.

Unfortunately, this is not that film.

Paterson is a very Jarmusch film – if you’ve seen any of his previous work, you know precisely what I mean: heavy emphasis on style, with a pacing that allows for the slow accretion of meaning to build, lachrymal. Unafraid of extended scenes without dialogue. Patterns recur without exterior development – following the relaying of a dream, Paterson continually meets pairs of twins – never explained, never developed beyond their mere, quirky presence. Scenes, interactions, are repeated with near-exactitude, allowing for a lateral development following small tweaks to the running. The repetitious nature of the film does a good job at underscoring the rhythms of Paterson’s working day, and, ultimately his life. It’s not necessarily tedium, no grinding trudge, as, as with most other things, the character accepts the monotony and the individual oddities with an easy-going calm.

And that’s kind of the issue, at least for what I was hoping for from the film. The performance isn’t flat, with moments where you can see Driver holding a mounting anxiety or a hot despair just in check, but it is muted. Those emotions never rise above the surface, and we are left with a film that is more like a photograph than a dynamic arc. The plot doesn’t really develop so much as follow; a week in the life – certainly, there is a climax of sorts, but, as the final act closes, it feels as if we are back at the start, that the resolution sets the clock backwards, rather than builds off of what came before.

Other characters are mainly pastiches or stereotypes – the hen-pecked publican, the besotted, broken hearted actor, the morose colleague. Even Paterson’s partner, Laura, accorded far-and-away the most screen time after the protagonist, is pretty one-note as something just this-side of the manic pixie dream girl. They are all there to play a role, though – the repetition of scenes, with ever so slightly shifted interactions, gives the feeling that this is much more Music With Changing Parts than it is Koyaanisqatsi – a slow swell that changes without the viewer really noticing. “Jagged” is not the word for Paterson.

I recall the score seeming slightly out-of-sync with the rest of the piece – much darker than the general tenor, lending a feeling of unease. Granted, I wouldn’t describe any of the characters as especially ‘triumphalist’ – even Laura, the most positive in demeanour of the lot, has an air of the slightly, poignantly, cracked – but neither is this some Loachian social-realist castigation. The meditative shots of post-industrial New Jersey cityscape, the circular lives of its denizens, are examined for the most part without an agenda – merely viewed, rather than marshalled. If there is tragedy here, it is a retiring one.

What of the poetry, then? This is actually one of the better parts of the film, by my lights. We see Paterson jotting down thoughts at various points – before he starts his route, whilst on lunch, whenever he can steal a quiet moment. Generally, our view of the writing is accompanied by a voiceover by Driver, reading back to us what he is laying on the page. Crucially, this isn’t just some stream-of-consciousness, first-draft-and-we’re-done deal – we see revisions being worked through, and improvements being made. A nod to the presence of genuine craft. By the second act, the references to William Carlos Williams are coming in fast – he is Paterson’s favourite poet, the city of Paterson was his home town, as well, and his body of work, and its following, play a key part in the resolution of the film’s primary crisis. Paterson’s own poetry resembles Carlos Williams’, though generally it isn’t as good – which is not to knock the film or Jarmusch, who wrote it – the lyricism should be looked for in the cinematography, not the materials it uses to get there. The portrayal of a blue-collar, autodidact poet is much more important than what he actually writes.

And, for all its bracketed delivery (the more I think about it, the more I’m reminded of how Richard Dreyfuss described using lithium as medication – chopping off the peaks and troughs, a more regulated bandwidth), this portrayal comes through. Without ever dipping into the maudlin or the precious, the film argues the case that you don’t have to be some ivory-tower aesthete or high-born toff to both (as if needed to be said) have a richly emotional internal life and to be able to articulate it. Though we’ve had fair warning about being a hero, a working-class poet doesn’t seem like such a bad thing to be.

All in all, an enjoyable watch, even if it didn’t supply what I was hoping for. If you’re looking for something soothing, meditative – hungover Sunday afternoon fare, or the like – this’ll fit the bill nicely. However, even sticking with Jarmusch, I’d say you’d be better served by Only Lovers Left Alive: a more sumptuous film, in my opinion.

ST:D – A Most Unfortunate Acronym

ST:D – A Most Unfortunate Acronym

Came across this article over at 3:AM yesterday, and its focus on the thematic as grounds for critique of the new Star Trek series struck me as refreshing. I’ve my own gripes, which I’ll probably get to in due course, but they are rather more menial than those detailed in the article.

In brief, Daniel (article’s author) makes a surey of some of the recent criticism, and praise, for Star Trek: Discovery, highlighting the way in which it differs from previous series on a broad level. Apparently, there has been some approval for the shift to a more politicised approach to the content, unlike the way in which The Next Generation or the Original pursued a very pulled-back, future Utopian-esque feel. Daniel mentions in passing the now-super-cringe-inducing way ST: Enterprise had tried to grapple with current events, and, from what I’ve seen, Discovery has thus far avoided this, I suspect it is waiting in the wings. I appreciate the fact that all SF is really about the era in which is it written, but the plotting of ST:E was so ham-fisted it’s a wonder it lasted for the 4 seasons it did.

The article references the very perestroika-era nature of TNG and Deep Space 9, which lead to the rather smug, Utopian triumphalism on display, and picks up on Bifo Berardi’s recent work detailing the decline of a technologist Utopianism of just this sort. Berardi has been, up to now, someone I didn’t have a lot of time for, Autonomism striking me as one of those theoretical frameworks you get less out of than the effort you have to put in to understand, but the work referenced – After the Future – might be worth taking a look at. The bookends of the techno-Utopian project, that of Marinetti’s Futurist Manifesto and the events of 9/11, seemed interesting, not least for the choice of these events in and of themselves.

This is not to say that the piece derogates the Utopian project outright – far from it, in fact. Counterpoised to Berardi’s pessimism for capitalist-technoUtopianism is the idealism of the early days of the Soviet revolution, espoused most particularly by Mayakovksy and the spirit of which is on display in Star Trek at its most succesful and heavy-hitting. Furthermore, there are good arguments that we need a Utopian focus, as it helps pull us through the drudgery of building a more equitable, worthwhile world.

For all its successes in carving its own trajectory, the article correctly upbraids the ST:D for taking the easy route on xenophobia. As was heavily discussed almost immediately, the presentation of the Klingons as religiously anti-Federation is meant to be a comment on the current state of American politics. However, as the 3:AM article points out, this has got the situation completely reversed. Thankfully, the data is coming to bear, and it is clear that the narrative of the ‘angry white working-class’ just doesn’t match the truth that it was affluent voters that allowed Trump his victory. But –

All of this points to the uncomfortable reality that hate and intolerance often emerge from within largely cosmopolitan societies, not from without. Nevertheless, in Discovery, the ideology of racial purity is assigned to an alien enclave entirely foreign to the Federation, suggesting that racism is not the left’s problem to fix.

It’s true that, despite good intentions, the previous series fell short of their “progressive” ideals in one way or another (<<cough>> <<cough>> rampant misogyny <<cough>><<cough>>). This, then, may be ST:Ds Achilles Heel.

Or it could be that the dialogue is wooden, the acting is crappy, the premise is dumb and rehashed, and the prosthetics are debilitating. Column A, column B?

I stopped watching after the 6th ep, back in mid-October, so I can’t really speak to any developments/improvements since. Still, it’s not too much to expect the series to have found its footing more than half-way through, is it?

This is the first I’ve seen of Sonequa Martin-Green, who plays the lead character Michael Burnham in ST:D, and I get that much of the issue lies with the really crap-tastic dialogue she is provided, but the human-acting-as-Vulcan really doesn’t cut it when it comes to building a likeable, engaging main character. Furthermore, can’t we put away this whole trope of “misfit learns to embrace their humanity”? The success of it in the characters of Spock/Data/Odo/SevenOfNine/whatever the fuck they used in ST:E was that they were part of an ensemble cast, and didn’t have to carry the whole of the series. As is, with the more linear narrative (as opposed to the potted episodes of previous series) of ST:D, Burnham is much too much the focus, and the struggle to come to grips with her human/Vulcan duality stretches pretty thin when it is constantly front and centre.

I know that I’m looking back on the previous series through rose-coloured glasses (I was a kid, alright?) and that they were super hammy, and the dialogue was often so stilted as to be somewhere in the stratosphere, but I can’t recall anything so grim as someone interjecting ‘Computer – add roasted tomato salsa. Cooked tomatoes are a great source of lycopene, remember that.’ Like, I get that they are trying to big up Burnham’s logical thrust, but, shit, it’s salsa. What the hell else is it going to be made from? Clunky.

Talking about clunky, can we address the prosthetics they’ve brought in for the Klingons? I’m not terribly down with the aesthetic changes they’ve made, as I’m not sure how you keep continuity (also, is this series meant to be in the same time-line as the other series? is it in the parallel universe of the reboot films? do we even know?) with what we see of the Klingons later on, but I can appreciate that the show runners wanted to differentiate things a bit.

The problem is, while the visual presentation of the species is striking – or at least, the faces are, costuming is all a bit naff – the actors can barely move inside them, and it leaves the faces rubbery, devoid of emotion. It also undercuts anything they try to say – what used to be an expressive, highly dramatic species is left croaking out lines that are stripped of any impact. And it’s not as if they couldn’t do better – the work on the character of Saru, by comparison, is stellar. I just don’t know why you’d elect to have your major antagonist look as if they have no motor control of their face.

If all this is meant to be in the main timeline, then the writers have done themselves a grave disservice. It irritates me no end when you get some tell-tale leap forward in a novel, some hint about a character’s fate, that completely undercuts any dramatic tension for the rest of the work, and it happens more often than you’d think. Here, if this is part of the same arc as TOS and TNG and all the others, well, we know that nothing actually comes of the Discovery and her crew, because the drive-technology that is so central to the whole series is never referenced in any other canon entity. It’s all moot. It’s bad story-telling, that hobbles itself before it’s even out the gate.

There’s a chance that Star Trek: Discovery will yet sort out its kinks and become a more balanced, interesting series. Sometimes it takes a season or so to hit stride, the start of TNG as a good example. All the same, it can do that on its own time – I don’t reckon I’ll be spending much more of mine on it. The 3:AM article, though, was interesting, and opened up lines of inquiry I hadn’t previously thought about.

Blade Runner 2049: Luke-Warm Take

Luke-Warm Take

These days, seems like there’s a check-list whenever a new sci-fi flick comes out, a formula for articles, think-pieces, and commentary to be made, ritualistically whipping up the internet into a self-righteous froth. These last few days have been more-or-less the same.

Caught the new Blade Runner earlier this week, at the local Vue. Not our usual cinéma de choix, but they’ve implemented a pretty hefty reduction on Monday ticket prices – perhaps they’re feeling the financial pinch.

I’m not a Dickhead (though I’m certainly guilty of being a dickhead…), so I didn’t go into this overly invested. Well, that’s not precisely true – I was concerned by the cutting of some of the early trailers, which seemed to be action-heavy in a way that didn’t sync with my memories of the original film (it’s been about a decade since I saw it last – couldn’t tell you which version, though I recall overdubs – and I’ve not read any Philip K. of novel length) which seemed a shame. I allayed my fears remembering that it was Villeneuve directing (which was a leap of faith in itself – I’ve not yet seen Arrival) and was reassured that the atmos, at least, would be on point. I wasn’t disappointed.

More on the ritualistic criticisms, though – as per usual, there have been accusations of vacuousness (untrue) misogyny (kinda true) and racial insensitivity (pretty accurate). Maybe it’s because I’m not paying as close attention, but I don’t really get the sense that other genres, outside of the speculative like sci-fi or fantasy, get the same sort of treatment. This is not to say there are no criticisms lobbed at your latest Disney effort, or the most recent Scandi-noir police procedural or what have you – when these films are egregiously out of step they are rightly upbraided – but they don’t seem to have the same rubric of criticism applied. Perhaps it’s because, as speculative fiction, sci fi looks at the possibilities for the future, and a future that leaves out large chunks of the present is both morally and structurally myopic. Perhaps it’s because the audience of this genre overlaps significantly with the Tumblr crowd of rambunctious moral arbiters. Who’s to say?

I, white cis het male that I am, feel that the film for the most part avoids accusations of misogyny. It certainly portrays many of its female characters in an overtly-sexualised manner, but, insofar as I can tell, this does not a misogynistic film make—the portrayal of misogyny is not misogyny tout court. Importantly, and this is where the film stumbles on other criticisms, the portrayal of women in Blade Runner 2049 is in keeping with that of the original Blade Runner, insofar as the society’s approach to gender is concerned. The world of the original was a grossly sexist place, and so too is that of the sequel. As much as the Blade Runner-verse happens in a time-line adjacent to our own real-world one, it’s probably a faithful representation of what would happen to our society in a hyper-commercialised future – hell, it’s probably what we’re headed towards at the moment. It’s not as if the multi-story holographic adverts that dance above the street-level replicant manifestations of the product don’t have real-world analogues. This is just a dialled-up version of what we already have, with the pop-princess du jour filling our various media with a commodified sexuality, reinforcing and guiding the trends of society’s actual sex workers, the logics of pornography stamped into us day-in, day-out.

Blade Runner 2049 doesn’t revel in its portrayal of misogyny. It’s not lurid, it’s not exploitative. It definitely has characters that use women, or woman-analogues, in a less-than-positive light (the protagonist foremost amongst them), and shows a society that, much like our own, is pervaded by the otiose relish of the female form, but to do otherwise would be dishonest to the story it is telling. A protagonist who possesses all the right views on women, whilst also on the arc that the story requires of him, would jar. A society that is as steeped in a runaway capitalism as that of Blade Runner but also respects women is a contradiction in terms – sexism, just as racism, is concomitant with capitalism; they can’t be pulled apart. Hell, this is a society that is literally built on slaves – it’s the whole thrust of the story – why would you expect it to have anything but trash gender politics? But, even in showing all this, the film doesn’t become complicit in it. While it doesn’t go so far as to damn what it shows – it’s more harsh on the hollowness of these relationships than the power imbalance inherent – it doesn’t actively enjoy it, either. It has ample opportunity to: the “love scene” between the protagonist and his “partner” could have been much more sordid, aimed entirely at titillation. Instead, it is used to underline the core concerns of the series, that of the nature of personhood and the ambiguities, the uncanniness, of possible human-adjacent realities.

The more accurate complaint revolves around non-white people in the film, or, rather, the lack-thereof. The setting of Blade Runner 2049, much like its predecessor, is Los Angeles and its environs. Picking up on some of the now-standard cyberpunk tropes, this Los Angeles is doused in Asian culture, from signage to the sartorial to gustatory. However, there are few, if any, actual Asian people in evidence. I’ve seen some clever epicycles deployed to explain this, the best yet being a comparison with the diffusion of American culture in our own world. In many countries around the world, so the argument goes, be they European, Asian, or, increasingly, African, you will find American businesses and products, replete with English signage, despite the absence of Americans, on the ground, perpetuating and guiding the effort. This is a product of the success of American cultural imperialism, the victory of American propaganda world-wide, as it portrays itself as something desirable, as synonymous with “success.” It was just this that led to the cyberpunk trope in the first place – during the Eighties, when so much of this stuff was codified, Japan was economically bullish, and the future, so it seemed, belonged to them. Thus, anything set in the near future looked like a fusion of Anglo and Japanese culture, with the hegemony of Japan redesigning the way American streets looked, the language that was spoken there, the food that was consumed.

All good, but the original Blade Runner, unlike its sequel, had plenty of Asian people on the streets themselves, as well as the signage and culture and what all. Where have they gone in the intervening 30 years? There’s been speculation that the Asian countries could have “gotten their shit together” and gone off-world – the existence of the extra-terrestrial colonies is a feature that looms large over both the original and the present Blade Runner – but this can’t account for every individual, and certainly doesn’t make sense of the real-world demographics of LA. The original film had a key character in Gaff, played by Edward James Olmos, who drew from his own mixed background to try and give a poly-racial feel to the film. Gaff is relegated to a few lines in a single scene in 2049, and I can’t recall any other Hispanic character – with dialogue or without – throughout the film. Evidently, much of the shooting was done in Hungary, so I can understand the logistical difficulties in importing the right mix of extras simply for atmosphere. Even so, the absence of nearly any brown or black faces in such a melting pot as Los Angeles is a bit stark.

All in all, I think Blade Runner 2049 comes through bruised but whole. Not a perfect film, but this isn’t a Bergman we’re talking about. The cinematography is beautiful, with very tasteful CGI. The pacing is, contrary to my original concerns, true to the original, and this, coupled with the seemingly-trademark Villeneuve soundscape, allows for a sustained meditation on what it means to be human. Performances were neither stilted nor overdrawn to camp. Could the story have been more nuanced? Were all angles satisfactorily explored? No. Does the plethora of criticism find purchase? Yes. As ever with these things, your best bet is to take a look yourself, and make your own opinions. Especially if you can grab some steeply-discounted Monday night tix.

Wittgenstein Jr, Reviewed

Wittgenstein Jr.

I recall, a good number of years ago, reading that ‘a philosophical novel is an impossibility.’ I maintain that it was Iris Murdoch who said this – I remember being struck by the idea that, if anyone were to know, it should be her – but I can’t for the life of me dig it up via Google. Irrespective – if this were true, bad news for Sophie’s World and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance – but not for Lars Iyer’s 2014 novel Wittgenstein Jr, because, despite the name and the nominal subject matter, it is in fact a love story.

The narrative follows, loosely, a group of philosophy undergrads in present-day Cambridge over the course of their degree, united by the presence of a shared lecturer. A lecturer they half-jokingly refer to as Wittgenstein Jr, as if he were a diminutive version, in all the eccentric mannerisms, of the more famous namesake. The jumbled-together nature of the cast – boys from different backgrounds and with different approaches to and desires from life – is highlighted in the work itself, resulting in moments of humour and pathos in equal measure as they strike off one another and maintain an uneasy friendship. This is balanced against the somewhat abstract maunderings of Wittgenstein Jr (whose real name is never offered up) which, while they don’t necessarily build to a coherent philosophical project, do massage the story forward.

No normal, straight-ahead tale, the prose style throughout the work is in a state of flux: at times, dialogue is laid out as a screenplay – named characters in block print, followed by words that we assume are passing in some manner of ordered temporality. At other times, we have the situation related to us by our protagonist, Peters, in a clipped, present-tense reportage that curtails any worries that he might not be the most faithful of narrators. Thirdly, we have the broad-stroke, hermetic declarations of the titular Wittgenstein Jr, as filtered by Peters, thrusting themselves between the actual events of the story.

It’s somewhat difficult to dissociate my own experiences from those of the novel – I fear that, being situated in Cambridge myself, I’m giving too much of the benefit of the doubt to the book. How much am I filling in gaps within the presentation, when I too have walked along the University backs, drank late at night on Cambridge’s rooftops, spent lazy afternoons meandering to Grantchester? Doubly, I’ve been an undergrad in a philosophy program, too. Much of the experience rang true – Iyer was a lecturer in philosophy at Uni of Newcastle before taking the position of Reader in Creative Writing, so he ought to know, if most recently from the other side of the equation – but how much is just my own insertion? Then again, the experiences we each bring to a reading inform it – there can be no distilled, pure version of any such affair, can there?

My biggest complaint, structurally, is brought on by my own experiences: no women in the class itself, and the female characters outside the main, male undergrad set are little more than set-dressing. In my own cohort, the few female colleagues amongst the majority male crowd were by far the best of us – but, and this is something endemic to analytic departments, few is the rule. Likely, my friends and colleagues performed so much better than the rest of us because of the unvocalised assumption that they were, even in the 21st century, interlopers, and thus had to outstrip the rest just to get by. I can only assume that Cambridge, at the undergrad level, is even worse on this. It would have been positive if Iyer was able to critique this state of affairs in some way, but I appreciate the lampshading nonetheless. The reported romances, those few that involve women, are dealt with on an abstract, allegorical level (and it is the disappointment thereof, the inevitably mundane nature of the amoureuse, that stalls the romance).

Rather than receive reports on the minutiae of the didactic process, the descriptions of the classes the group take with Wittgenstein Jr are opportunities for gnomic, aphoristic utterances that do more to provide an atmosphere to the book than anything of a linear, plotted construction. There are through-lines, such as the idea of the ‘English lawn,’ which resurface at various points. The metaphor is used as a heavy-handed critique of the modern Oxbridge reality, without necessarily hearkening back to a ‘better’ past:

“The English lawn is receding, Wittgenstein says. And with it, the world of the old dons of Cambridge.

New housing estates, where once was open countryside… A new science park where once were allotments and orchards… New apartment blocks near the station, their balconies in shade … And towering barbarisms: Varsity Hotel, looming over Park Parade; Botanic House, destroying the Botanic Gardens; Riverside Place, desecrating the River Cam…

They’re developing the English lawn, Wittgenstein says. They’re building glassy towers on the English lawn. They’re laying out the suburbs and exurbs on the English lawn. They’re constructing Megalopolis on the English lawn.

And they’re developing the English head, Wittgenstein says. They’re building glass-and-steel towers in the English head. They’re building suburbs and exurbs in the English head…

The new don is nothing but a suburb-head, Wittgenstein says. The new don – bidding for funds, exploring synergies with industry, looking for corporate sponsorship, launching spin-off companies. The new don, courting venture capitalists, seeking business partners, looking to export the Cambridge brand. The new don – with a head full of concrete. A finance-head. A capitalist-head.”

Iyer does a good job at presenting the self-important priggishness of overly-clever young men, puffed up on their own abilities and lacking the self-awareness to temper their more brash statements. Your humble reviewer may or may not be able to attest to the veracity of the following passages…

“EDE: Have you noticed how the rahs are all saying literally now? I was like literally exhausted. I was like literally wasted. But nothing they say actually means anything! Literally or figuratively! Most of the time, they don’t even finish their sentences. I was literally so… They just trail off. They barely speak, most of the time. Mmms and ahhs. Little moans, nothing else. Oh reeeealllly. Lurrrrrvely. Coooool.

And they use the word uni, which is unforgiveable, Ede says.”

“We speak of our desire for despair – real despair, Ede and I. For choking despair, visible to all. For chaotic despair, despair of collapse, of ruination. For the despair of Lucifer, as he fell from heaven…

Our desire for annulling despair. For a despair that dissolves the ego; despair indistinguishable from a kind of death. For wild despair, for heads thrown back, teeth fringing laughing mouths. For exhilarated despair, for madness under the moon.

Our desire for despairs of the damned. For crawling despairs, like rats, like spiders. For heavy despairs, like those on vast planets, which make a teardrop as heavy as lead…

Our desire for the moon to smash into the earth. For the sun to swallow the earth. For the night to devour both the sun and the earth.

We speak of our desire for extinction, for cool mineral silence. For the Big Crunch, for the end of all things. For the Great Dissipation, when electrons leave their atoms…”

Truthfully, the only thing that saves these extended sections from contemptibility is the earnest, charming honesty by which they are delivered. As much as they signal – on their surface – entitled, inexperienced boasting, the reality is that of young, nerdy men bonding, building a friendship to push back against the often-hostile, imperfect world they wish they could change for the better, or at least to their conception of what that might mean. Moments of shared, unselfconscious awkwardness – such is the mortar of friendship.

There are passages where the reader is offered glimpses of Wittgenstein Jr’s mounting paranoia – never so sharp, though, as to turn the tenor of the book, which remains fundamentally light in its touch. The sheer outrageousness of it, though deadly serious in delivery, can’t but undercut itself. One can almost picture Bernard Black uttering the below –

“The dons are always ready to pounce, he says. Always ready with their greetings. Hello, they say. Nice weather we’re having, they say. How are you?, they say. How are you getting on?, they say. What have you been up to?, they say. Each time: an assault. Each time: a truncheon over the head. Hello. Nice day. Hello. Hello.”

As I had mentioned earlier, though, the work really shines when it is relaying the essence of Cambridge, descriptions of the physicality and references to the culture combining to provide a hefty psychogeographical distillation. One where you can almost feel the sandy crumbling of acid-rain washed architecture under your fingers, the heaviness of all this accumulated, academic prerogative bearing down on you.

“Flooded pasture. Meadows full of standing water. Salt-water wetlands. Tidal creeks and meres. Rivers braiding, fanning out.

You get a sense of what the Fens used to be like, before they were drained, Wittgenstein says. Settlers building on banks of silt, on low hills, on fen edges. Towns like islands in the marshland.

We imagine the first scholars, expelled from Oxford, founding the new university in Cambridge. We imagine the first colleges growing out of boardinghouses. The first classes, teaching priests to glorify God, and to preach against heresy. The first benefactors, donating money for building projects. The first courtyard design, at Queens College, the chapel at its heart. The first libraries, built above the ground floor to avoid the floods. The lands, drained along the river, and planted with weeping willows and avenues of lime trees. The Backs, cleared, landscaped lawns replacing garden plots and marshland. Cambridge, raising itself above the water. Cambridge, lifting itself into the heavens of thought…”

I started off this review by denying the idea that it should be a ‘philosophical novel,’ and instead declaring it a love story. I think I’ve shown some of the appreciation it has for the particular moment in life the characters share; the physical place they find themselves in. There is a more prosaic, more carnal love story that winds its way through the piece, but, I think, to give it away here would be a disservice to the reader. As much as it comes to the fore towards the end of this relatively short piece, it does a good job of injecting a degree of energy, of providing motion that makes sense of and solidifies the earlier passages.

Suffice to say, if you yourself have come from a humanities background, or really from any space where a volatile, passionate friendship has sprung up – one that hangs together despite itself, and burns the brighter for it – and it’s something you’d like to see represented; if you’ve a desire to get a feel for what Cambridge is like as a place and a head space; if you’re interested in intriguing and challenging narrative forms, there are worse tales to read than this.

Plus, it’s quite funny.

Gatiss, what have you done?

The Vesuvius Club

It’s a hackneyed turn of phrase – we’ve all heard it, whether directed at ourselves in moments of deep personal opprobrium, or, later, jesting with friends, bonding over the fact that we are all of us imperfect beings – but, Mark Gatiss, I’m not even mad. I’m disappointed.

I picked up The Vesuvius Club: Graphic Edition from the local library a while back. The comic version of Gatiss’ 2004 novel of the same name, the work is a condensed version of Gatiss’ text coupled with Ian Bass’ art. Black and white, the depiction is a blend of real-to-life and caricature, stark lines with negative space in solid fill. Far from the worst I’ve seen, it remains perfunctory – there isn’t much here that benefits a second viewing; it’s all surface.

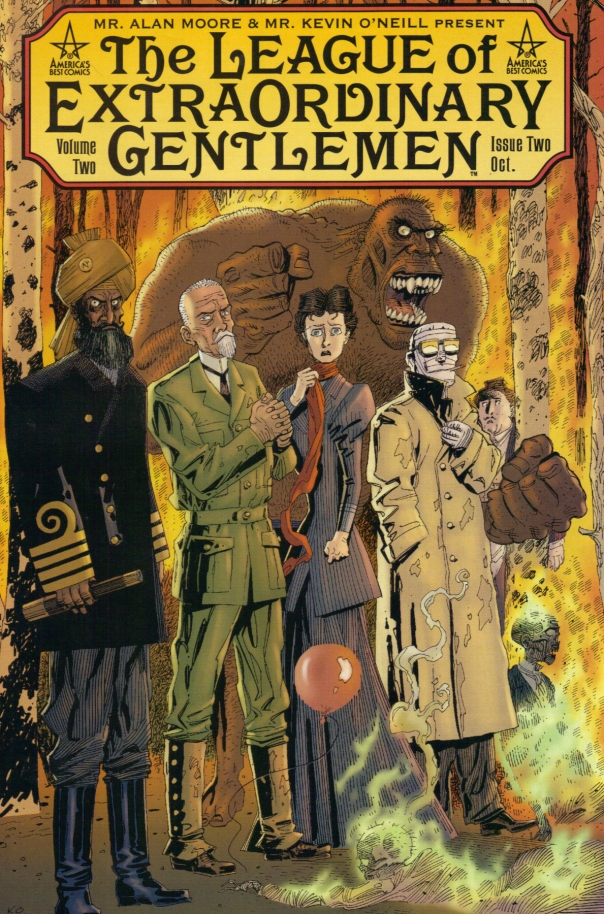

The volume covers a single arc, and runs to 100 pages, as well as character splashes and newspaper-style adverts on the inside covers. It’s here that the frustrations set in. The design, at least to my mind, sets you up for something similar to Moore and O’Neill’s The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen – both series cover the same period, the late Victorian/Early Edwardian, both have a puckish reverence for the aesthetics of the era, both blend the mundaneity of the period with the fantastical. It’s a bit of a difficult comparing much of anything in comics to Moore’s work – there is almost always a clear divide in quality, in depth, in novelty, etc., etc. What little I’ve read of Gaiman’s work sometimes comes close, but I’ve seen little else. Which is all to say that it might be a little unfair to compare this, an adaptation of a work, from a writer of various media, to that of a focussed effort from a master of the form. The failure to achieve greatness, however, is not what I’m so frustrated by.

Moore, as a story-teller, is definitely not without fault, and League, for all it’s depth and detail, is a flawed work that, at least in the main run, collapsed under its own weight. While clearly riffing off the period each issue was set in – it was, after all, an effort to blend all of literature – the whole arc was steeped in Moore’s particular style of progressivism. Though the characters themselves may have been constrained by Edwardian values, the narrative itself didn’t play to those rules – indeed, so much of the story is driven by Mina Harker’s efforts to assert herself in a “man’s world” playing a “man’s role.” When odious, racist depictions surfaced, they were almost always undercut and inverted; acting, rather than as signifiers for themselves, to show off why these caricatures were wrong in the first place.

To its benefit, Vesuvius is not totally without this – the protagonist is bisexual, and one of his accomplices gay, and this is not treated as morally reprehensible by the tone of the narrative, if not always their fellow characters. However, I fear that Gatiss may have played it too straight in his appreciation for and representation of mores of the period. Characterisation of other elements in the story are lifted almost whole-cloth, without any evidence of satire or nuance, from the racist and bigoted tropes of the era. There is a stereo-typical ‘mandarin’ looking awfully a lot like something Mickey Rooney may have played who, inevitably, runs the Opium Den, and then the villain, in the reveal, turns out to be a transvestite. And mad. ‘Cause nothing’s more twisted and evvilll than a mentally distressed person with a penchant for women’s dress.

Cultural appropriation is a hot topic in the literary world at the moment, what with Lionel Shriver’s recent key note pushing back against what she feels is political correctness gone mad, and the inevitable blow-back she received as others circled the wagons (for my part, I think both parties are wrong). Vesuvius, though, is obviously not a case of appropriation as much as it is stale tropes that were rankly offensive when they first surfaced, let alone more than a century later. What is worse is that we all know Gatiss is better than this – his work in Doctor Who and Sherlock (“The Abominable Bride” aside…) are some of television’s better efforts, so it’s not as if the man is a serial offender or endemically prejudiced.

I can only hope that this is a singular misstep in an otherwise reputable career. Evidently Vesuvius has been in production for the small screen for a while. Hopefully they clean it up a bit.